This Couple Has Been Homeless And Jobless – Last Week, They Graduated From A D.C. Charter High School.

By Hannah Natanson

The line was alphabetical — but if it hadn’t been, Danielle and Stephen Corbin would have found a way to stand together anyway.

The couple had already weathered so much: periods of homelessness, joblessness and hopelessness. Moments when the homework load at Goodwill Excel Center, an adult public charter high school in the District, seemed overwhelming, especially on top of their full-time jobs. Sometimes, they wanted to drop out.

But they didn’t.

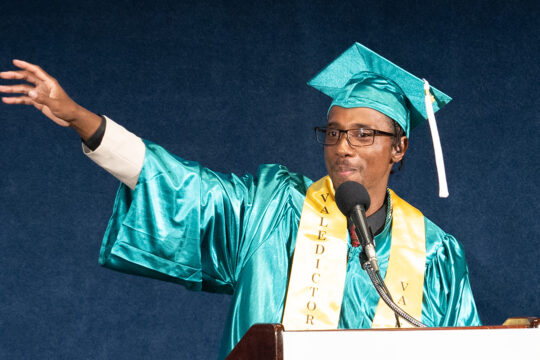

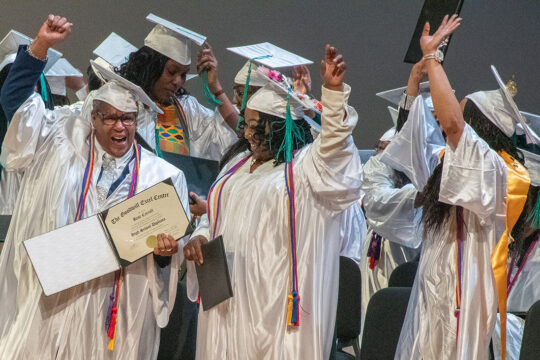

Now, Danielle, 40, and Stephen, 33, were number 10 and 11 in the long line in the Lisner Auditorium at George Washington University. They were surrounded by dozens of other soon-to-be graduates in white (for women) and green (for men) caps and gowns.

The Corbins stood side by side with their bodies half-curved toward each other like the halves of a clam shell. Neither thought they would ever be here.

“I couldn’t believe I finally did it,” Danielle Corbin said later of her graduation last week. “That whole day, I was just thanking God for the opportunity to go back to school.”

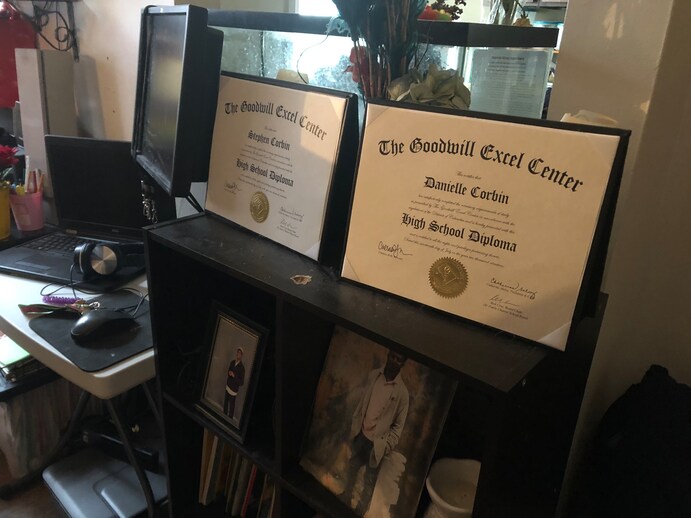

“And I was just thinking, ‘This is what I have waited for,’ ” Stephen Corbin said, sitting beside his wife in their apartment in Northeast Washington. “It completed a puzzle that I lost the pieces to so long ago. Now I’ve found them.”

The husband-and-wife duo graduated — both with honors — last week as part of the fifth class to come through the D.C. school, which opened in Foggy Bottom in August 2016 and graduates multiple classes a year. It is one of several such schools that Goodwill Industries, the national nonprofit that sells used furniture and clothes, opened across the country in recent years.

The school year is divided into five eight-week sessions. Students who complete the program receive Industry Recognized Credentials and full high school diplomas. The Foggy Bottom institution is the first and only adult education charter school in the nation’s capital to offer these.

The July 2019 class, the school’s largest at 72, was remarkable for more than its size. It included D.C.-area residents ranging in age from 16 to 71, as well as a valedictorian who gave birth about a month before delivering her honorary address.

To the Corbins, it was a second family.

On Friday, Danielle and Stephen Corbin were trading jokes, selfies and hugs with the other students. Both Corbins graduated with yellow cords for peer tutorship, meaning they regularly helped at least five of their peers finish homework or study for exams. Sixty-nine of the 72-strong cohort earned yellow cords.

It was this kind of teamwork that made the Goodwill Excel Center so different from high school the way Stephen Corbin remembered it the first time around.

“I was bullied, I was the outcast student that suffered,” said Stephen Corbin, who has ADHD and dyslexia and struggled in almost all of his classes.

He began hanging out with “the wrong people,” mostly because he lacked adult male role models, he said. Stephen Corbin’s father was not in the picture. Though his devoted mother tried to stop him, Stephen Corbin picked up “a nasty habit” of stealing cars, he said.

He quit high school at 16. He wound up spending most of his teenage years in juvenile detention, coming home for three months at a stretch before nabbing another car and getting picked up by the police again.

“I put my mother through so much heartache and pain,” he said.

Several years earlier, Danielle Corbin — at that point unknown to her husband, though both lived in the D.C. area — had also dropped out of high school, though for different reasons. She had gotten pregnant at 17 with her first child: a son, Diondre Ouzts.

She realized that her own mother, a single parent, would not be able to help. So she left classes behind and snagged jobs at McDonald’s and Burger King. Later, she found employment as a security guard.

At 20, she got pregnant again with a daughter, Eniyah Ouzts. And that “pretty much ended the idea of school” — or so she thought, for many years to come.

Both Corbins underwent periods of homelessness. Danielle Corbin recalled living in a van with her two children, sleeping on a rotating cast of friends’ couches. Stephen Corbin spoke of nights spent “on the streets, begging for change.”

Things got better when the two met about 17 years ago through a mutual friend. They have been together ever since.

In 2011, the two moved into an apartment along with Danielle Corbin’s two children, whom Stephen Corbin has raised and sees as his own. In 2013, they married, flanked by the children.

And in 2017, the couple went back to school. After hearing about the Goodwill Excel Center from a friend, Danielle Corbin walked into its D.C. headquarters and signed both up for a second try at education.

It stemmed from a general desire to “get our lives together,” Stephen Corbin said. Both had just scored jobs at Community FoodWorks, a nonprofit that works with local farmers to deliver fresh vegetables to low-income D.C. residents, he after a period of unemployment.

It was also inspiring to watch Eniyah Ouzts, now 19, graduate from high school two years ago, Danielle Corbin said.

“We got a lot of nieces and nephews and godchildren that look up to us, and you cannot only preach about it, you have to live it,” Stephen Corbin said.

It was not easy. At times, their work schedules threatened their ability to keep on top of classwork. Both had to rise early to reach faraway farms and sometimes returned home as late as 9:30 p.m.

As with every other challenge they’ve faced, though, they teamed up to get through. When Stephen Corbin had to skip school for work, Danielle Corbin filled him in that evening on what he had missed. And they helped each other with homework, often holding marathon study sessions in their bedroom, each perched on opposite sides of the bed.

Danielle Corbin, who has always excelled in math, coached her husband through tricky equations. Stephen Corbin, an avid reader, helped his wife understand and analyze literature.

Chelsea Kirk, the director of the Goodwill Excel Center, said she has never seen a couple so determined to stick together. The pair always plotted to wind up in the same classes, she said — a strategy that can be counterproductive but worked well for the Corbins.

“They were a really unique couple because they were completely each other’s support; they knew they needed each other to do well,” said Kirk, who taught the couple at one point.

Onstage last week, having survived it all, they sat together in the front row. For most of the ceremony, Stephen Corbin kept his arm firmly wrapped around the back of his wife’s chair. When she stood to cross the stage just before he did, Stephen Corbin wiped away a tear.

Sitting in the audience — often tearful themselves — were Danielle and Stephen Corbin’s families. After the ceremony, everyone headed to the Golden Corral, the Corbins’ favorite restaurant, for a celebratory meal.

Even as they revel in their accomplishment, though, they have already begun planning for the future.

Danielle Corbin has applied to Trinity College and to the University of the District of Columbia. She wants to get a degree in early childhood development and open her own daycare, a long-time dream.

“It’s my passion. I love working with kids,” she said.

Stephen Corbin, meanwhile, hopes to become a truck driver. His history of stealing cars left one positive legacy — a deep-rooted love of driving.

Still, whatever happens, there is one certainty: The Corbins will face it as a unit.